June 8, 2015

Sequence Six: Stay

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 26 MIN.

"For the sake of the gods," Mark laughed. "They aren't going to kidnap you."

I smiled tightly -- as tightly as I constricted the new tie I was trying on, inadvertently turning the goddamn thing into a hangman's noose. With a gasp, I yanked the tie off again.

Mark's eyes widened in the mirror. "Whoa! Take it easy! You wanna kill yourself?"

The two of us still looking at each other in the mirror, I offered him a half-snarl, half-smile.

"Hey now, is it really going to be that bad?"

I turned from the mirror, tossed the tie into my open carrybag on the bed, and fumbled with the top shirt button. "It's family," I told him.

Mark plucked up the tie, carefully rolled it into a neat spool, and tucked it into the carrybag. Closing and zipping the flap, he hefted the bag with his strong left arm. "Not too bad," he said. "You're learning to pack like a man."

"Fuck you," I laughed.

"Next I'll have you shaving just the parts that really need it."

I grasped him by his blond-bearded jaw, and fixed his deep-sea eyes with mine. "Thanks."

"Yeah," he said. Never one to linger, he held my gaze only a beat before adding, "Now let's get you to the airport."

I wasn't ready to let him go. I kept him right where he was and planted a kiss on his lips. It was a long one. He grinned at me when it finally ended. "Are you sure I can't come with you?" he asked.

"You really don't want to -- believe me. They're not ready." I patted his furry cheek. Gathering up my suit coat from the back of the chair that stood by the closet I turned toward the bedroom door.

"What, they don't know you're gay?" This was another joke; of course they knew I was gay. They even knew about Mark.

"They're... provincial," I said, as we headed up the hall.

"What, like French?" he asked, lugging my bag, treading lightly behind me. We slipped out the door into the early light

"They're... insular," I clarified, as we paused on the porch to lock the door.

"So I understand, but..." Mark looked like he didn't want to say what he was thinking.

I knew what he was thinking. "If things go well, who knows? I might actually get back there again in the near future," I told him. "And then, well... you can come next time."

"I bet if they met me, they'd like me."

"Sweetie..." I took hold of the back of his neck, rubbed him affectionately. "They absolutely would. But it's not you. It's me."

***

The flight to Pugnat, Pennsylvania wasn't long, but it gave me enough time to start chewing over old memories. Mark isn't the sort to pry, and I have never told him about it, so he didn't know that they had, in fact, kidnapped me once. My mother had left my father in a huff after months of escalating fights and tension. She piled me, my brothers, and my sister into the car, and headed for the highway. But she didn't reach the edge of town before my Uncle Charlie, the cop, pulled her over.

I don't remember what pretext he had, or if he even bothered with a pretext; all I really remember is the way his hands reached in and grabbed me, his grip rough and his fingertips stabbing, lifting me from the car as my mother's shrieks and curses colored the air. He all but threw me into the back of his squad car, and he tossed my siblings in after me.

Uncle Charlie didn't even bother with our luggage. He slammed the door shut and then we saw him through the squad car window as he leaned toward my mother. Was he whispering something to her? None of us were quite sure. If so, whatever he whispered caused her to blanch. She turned, got into the car without another word of protest, and sped off. Our uncle strode back to the squad car, threw himself behind the wheel more or less the same way he'd thrown us in the back seat, and took us home. We could parse nothing from him -- he was as closed and silent as a clam.

His wife, our Aunt Clara, took us shopping for new clothes a couple of days later. All of the aunts helped look after us, and so did grandmother. We never saw mother again, never heard from her, never even heard about her except when eavesdropping on the adults. Sometimes the subject of our mother would surface briefly in their conversation, but only briefly; she'd be recalled, then summarily banished once more.

"Katherine? Well, she was never one of us."

And that was a puzzle, because even before she left, even before the kidnapping and all the snide remarks that followed for years after, we had already picked up on the fact that the reason dad married her was exactly that: She wasn't one of us.

***

"You here?"

The text from my brother Gilbert blipped onto my Intelliphone as soon as I powered it up. This irritated me. The plane had barely landed at the Pugnat airport, was still rolling toward the gate. I had a thirty-mile drive ahead of me before I got to Grant Hills. What was the rush?

I texted him back a terse affirmative and then, "Picking up rental car. At hotel in a couple of hours."

"Drinks at 5, rehearsal dinner at 6," he texted back. "Sebastiano's."

I didn't reply to this; instead I texted a complaint to Mark. "Family bossing already, not even off the goddamn plane," I tapped out.

"Relax," he sent.

I replied with a wobbly, exasperated emoticon and he shot back a string of Xs and Os.

***

When I decided to leave our cozy little community and go to college, Aunt Clara spent an inordinate amount of time trying to get me to hang back, stay in town, maybe go into business for myself.

"Doing what?" I asked her. "Cutting grass?"

She seemed to think I was serious; she offered me a weekly lawn care gig at her house, for $50 a pop. I shrugged this off, shrugged off all her arguments and entreaties. I got more of the same every time I came back for the holidays, for summer break... I finally stopped coming back after sophomore year. They sent their congratulations but refused to leave Grant Hills for my graduation. Not Aunt Clara, not even dad made it out to Virginia. Fine, then, I groused.

Eleven years later, this was the first time I was coming back to see them.

That killer tie was wrapped around my neck once more. Staring this time into the hotel mirror, I felt as though invisible fingers were crushing off my air. I left the knot a little slack.

***

"Hey little brother."

"Hey, Marisa."

She leaned down to kiss me. I caught her sarcastic whisper of, "No, really, don't get up and greet me like a gentleman."

I didn't. I pretended I hadn't heard her, and she pretended there was nothing to hear. Our older brother Gilbert was already half in the jar, beaming across the room at Lansing, the baby of the clan, who sat with his pretty bride to be. He was blushing red as his mop of hair, grinning and embarrassed at all the attention he was getting. The whole extended family was there.

I was surprised when I caught sight of my baby brother's intended. "She's from around here, isn't she?" I asked, squinting at the bride. "She looks familiar."

Gilbert paid no mind. He was whooping along with everybody else over whatever joke had the room in stitches.

Marisa heard my question, and registered its multiple meanings. "Yeah," she said, a little flatly. She took a sip of her champagne. "After however many generations, it wasn't making any difference. So whatever it is, it's not genetic. Dad finally just abolished the First Decree and said that the guys can marry local girls if they want."

This was news to me. I wanted to ask when that change in policy had taken place, but I had another question first.

"So, who is she?" I asked.

"Shana Dawson. She's been Lansing's sweetheart since third grade."

Well, that was good timing on Lansing's part, I thought, as I lifted my own flute of champagne -- cheap stuff, I noticed. But then again, I reflected, Lansing, being the baby, always got away with murder. If he'd really wanted, I bet myself, Lansing could probably have married whoever he wanted to, First Decree or not.

Reading my mind, Marisa shot me a look that plainly said to behave myself. Aloud, she said, "I guess you never felt like you had to worry about the marriage decree. But poor Gil..." She glanced at our older brother, who was seated now, stirring his cocktail absently with a fingertip and studying his Intelliphone. Even in the blue light of the tiny screen he was clearly flushed, and looked more than a little drunk. "He's still not married."

"He could have stood up to Dad," I argued. "How much of a stickler was Dad going to be? I mean, if Dad hadn't relaxed his stupid marriage rule and Lansing was determined to marry Shana anyway, what was he going to do?"

"Apples and oranges," Marisa replied. "Things are different now, but when the decree was still in effect, no one wanted to marry against Dad's wishes. You remember our cousin Victor?" The question was rhetorical, because of course I did. As teenagers, Victor and I were inseparable. I felt certain Marisa chose whatever horror story she was about to tell precisely because it involved Victor, and she knew it would make an impression.

"Well, Victor got it into his head he was going to marry Elise Markle, and nobody was going to stop him. But Dad stopped him."

If she was trying to unsettle me she was succeeding, but not because the story was about Victor. My gut feeling about this entire trip was growing worse: Steeper, sharper. I felt the ground was tilting and I was on the verge of sliding into some new pit of doom and terror.

"What did Dad do?" I asked.

Marisa hesitated. "Let's just say Victor is... a lot more pliable than he used to be." She raised her eyebrows in a gesture of caution and then downed her champagne in a swallow.

The booze must have fortified her, because a moment later she grew even more brash than usual. "I wonder if you were straight if Dad would have allowed you to leave."

I whispered to myself that Dad couldn't stop me. And he tried.

Marisa heard, but had another subject she wanted to pursue. "So you didn't bring your man," she said, waving her empty flute to flag down a server with a tray of fresh flutes and wine glasses. "Why not?"

The server stood at our table. Marisa diverted her attention long enough to say, "I'll have a wine. It's been a day."

"Red or white?" The server was a well-groomed kid with pale, thin blond hair. Like almost everyone in the room, he looked familiar, but I had no idea who he was. Given his current age he must have been six or seven years old -- if that -- when I'd left.

Marisa reached out and plucked a glass of red off his tray. "Thank you," she said brightly, as he did a quick jig to re-establish the tray's equilibrium.

"White," I said to the slightly flustered kid. He handed me a glass and then lingered uncertainly for a moment.

"Thanks sweetie," Marisa said. "Scoot along now. But come back soon!"

I whispered that her matronly act didn't convince anyone. She whispered back that it seemed to work just fine for all the youngsters who'd come along since I'd been gone.

We each took sips of our drinks as this exchange occurred. Then Marisa picked up on me still trying to place the waiter.

"Maisie Vogel's boy," she explained.

"Huh," I said. Did Maisie Vogel even have kids? She used to holler at me because her vicious dog barked when I walked by their house and I would heft a rock in warning.

"Don't you throw that rock at my dog!" she used to shrill out her window.

"I'm not gonna unless he tries to bite!" I'd sass right back, trying to suppress whispers about Maisie herself being an even bigger bitch than her goddamn dog.

"So," Marisa said, pulling me back to the moment. "Your guy? Mark?"

***

Mark.

I met him in a stairwell, of all places, because I just missed the elevator and only needed to climb three flights. I thought I might just as well get some exercise. He was loitering in the stairwell, picking at his Intelliphone. When I climbed up to the landing where he stood, he looked up. The moment our eyes met it felt like a bolt of lightning hit me.

He felt it, too.

We stared at each other for a second and then he said, "Well -- hi!"

"Hi yourself," I told him.

We both started grinning.

Things proceeded from there.

***

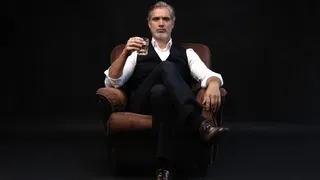

"He looks kinda like that actor," Marisa said, studying the photo on my Intelliphone. "You know, the one in all those shows. He's always a badass, and he always gets killed after a few episodes."

In the photo, Mark did look a little thuggish -- but like a smiling, handsome thug. His blond hair was combed back and his eyes were fathomless, compelling, much as they were in person. You had to look closely to see their color.

"It's unreal," Marisa said. "He looks just like him."

"Uh huh," I said. I knew who she meant, but that actor doesn't really look that much like Mark. At best, they share a glancing resemblance.

"So he's good looking. Is he smart?"

"He's smarter than I am," I said, half boastfully. After all, it was true.

"And rich?"

She was joking, but she was closer than she knew. "His family is rich," I told her, wanting to emphasize the distinction. "Really rich. But he doesn't want their money -- we don't want their money. We get along just fine on our own."

"Out of pride, or -- ?"

My look told her there was more to it than that.

Marisa promptly took a different tack. "So, you didn't want to share him with us?"

I couldn't help whispering that I hadn't wanted to come, myself, and certainly didn't want to subject him to my family.

That got her mad.

I shrugged.

"You really are an asshole," she said.

I started to whisper, but then said right out loud, "You don't have a clue."

"I have more of a clue than you do," she said, a little haughtily, a little on her moral high ground. "I've been right here where I can see what's going on. Not halfway across the country."

"Albany," I scoffed. "Hardly halfway across the country."

We both took a break to reign ourselves in. I sipped at my drink; Marisa took a good healthy gulp and looked around for Maisie's boy and his tray. That reminded me to ask her about her own son, William.

"Where's Will?" I asked.

"Oh, off over there, I guess, with his friends." Marisa tilted her head vaguely toward the far side of the room where a gaggle of teens clustered, chatting raucously among themselves.

"How old is he now? Fifteen?"

"Fifteen." She offered me a half-soaked smile and raised her glass in a gesture of celebration.

"And Arthur?" I already thought I knew where Arthur was -- at home, in his den, surly. Arthur was intimidated by our father, and -- by extension as much as my own merit -- by me, too.

"He's here," Marisa said, surprising me. "He's talking business with some guys."

Talking business. It sounded like Arthur. So neurotic, and such a workaholic, the only way he knew to keep his mind off his axieties.

Victor suddenly appeared at the table -- cousin Victor, who was my best friend all those years ago. "Ben!" he cried. "Benjamin!"

I got up. Marisa whispered something snotty about how now I bothered to get off my ass and greet someone. Victor didn't notice, and I blocked it out.

"Victor, man, how are you? Good to see you, cuz!" He had me in a bear hug and I hugged him back hard in self-defense.

He drew back to look at me, still smiling. "Ben!" he said again. Then a puzzled look came over him, as though he didn't know what else to say. "Uh..."

"Sit down, tell me what's been up," I invited.

"Uh... Benjamin!" His grin came back, incandescent. Then he shrugged, and gave me a half-wave, before moving off again to the next table, where he greeted Aunt Estella and Uncle Darren.

So this was what Dad had done to Victor.

"He's not stupid," Marisa said, her anger set aside when she saw my shock. "He's just a little, I guess you could say, he's a little disconnected. And he lacks a certain... "

"Volition," I said. "The old man took away his volition. Of course, we can't have anyone thinking for themselves, now, can we?" There were uglier words struggling to climb out of me. I bit down hard out of reflex, automatically censoring... not even thinking... what I really wanted to say. Treacherous sentiments about finding the old man and wringing his leathery neck for what he'd done -- not only to Victor, but to mother, to us, to all of us. Who did he think he was?

Where was the withered old fucker anyway? Had he even shown to his youngest son's rehearsal dinner?

That was when Dad made himself known. I heard his whisper from across the room. I whipped around to lock eyes with him: He was staring at me with the soulless gaze of a stone god.

Aunt Clara came out of nowhere just then. Her face was the same, only older, grayer, lines deeper around her eyes and across her forehead, lines of worry. "Benjamin, dear," she cried, her delight genuine but forced up a notch. Throwing herself between my father and me. Playing peacemaker.

And up to her old tricks.

She took at seat with Marisa and I, chattering on about how good I looked, how I was all grown up, what pride she took in my career as a producer of video postcards and greeting-clips and even, recently, a few documentaries -- earnest documentaries, a little dry, she thought, but they were important because they spoke about urgent things the newsfeeds didn't want to touch. Labor riots. Wall Street power struggles. Court cases that kept reaffirming the human rights of big companies, but not of the actual human beings who worked for them. Wholesale wage theft and the latest banking crisis. "What can you expect with the Theopublicans dug in so deep, and that last election was clearly stolen!" she exclaimed.

Her entire line of conversation led right where I knew it would.

"Dear, you know we miss you awfully, and we worry about you in that cold, cruel world away from your family. This isn't such an awful place, is it?"

I whispered, You're goddamn right it is. It's awful.

She blinked, and her smile rippled, but she pressed on ahead.

"And we just think... I mean, your father even says that you belong here, Benji."

Oh, don't call me that. I rolled my eyes.

"It's not like we're not part of the world," Aunt Clara continued. "We are. But we're a little sheltered from its crueler parts. We look out for each other. This is still a place where people count for something. We're neighbors, we're friends... we're family."

"Yeah, and..." you've got him running everybody's lives. Or trashing their minds if they go against him.

Her lipstick-reddened lips remained curved in a smile but pressed into an angry, thin line and her cheeks grew ruddy. Your father isn't young any longer, she snapped back, finally abandoning spoken words and lapsing into whisper. His health is starting to fail. You have to understand that he's done everything in his power to protect us.

Yeah? I scoffed. From what? Isn't his whole argument that by staying here and keeping to ourselves it's actually us who are protecting everybody else?

Things aren't so simple as all that, young man, Aunt Clara flared at me.

"You guys should just say it out loud," Marisa interrupted. "Everyone can hear you whispering anyway."

Aunt Clara switched back to spoken words. "You should talk to your father, Benji. And you should show him some respect."

Why? I whispered, low, addressing Aunt Clara alone. Because if I don't, he might "wish me into the cornfield?"

She gave me a look of pique, then turned and walked away.

"You're really endearing yourself to everyone, big brother," Marisa said. "At this rate you won't get invited to the next one."

I spared a glace at Gilbert, who'd clearly heard my exchange with Aunt Clara. His lips were pressed together into a thin, strained line, his eyes cast down to the table. He had a fresh drink in his hand. It must have been his fourth, maybe his fifth.

"Yeah," I said. "Like that's gonna happen any time soon."

***

It really was time to confront the old man, I decided. I got up and made my way across the room. He was still watching me -- he looked impassive, but I could feel the tidal forces of his conflicted emotions. He wanted to hug me; he wanted to slap me; he wanted to take me over his knee. He was angry, embarrassed, fatigued... scared.

That almost scared me, in turn, because my father was never frightened of anything. Of course, he could project or withhold anything he wanted; his ability for a great degree of privacy in thought, mood, and intention was a huge part of his influence and his ability to strategize. In a town of telepaths, you don't distinguish yourself by being the loudest or the most transparent: You stand out by being able to maintain rigid control over your thoughts and feelings as well as your words, deeds, and affect. Cultivating the ability to cloak your thoughts is useful, too, but Dad enjoyed a further talent -- the rarest of all. He didn't just pick up on what people mentally broadcast; he could reach into a mind and mess with it, implant ideas, screw with the wiring, even (or so I suspected) cause a fatal hemorrhage, like a few of the own's founders supposedly had been able to do.

Back when men were men, I thought bitterly. One of the old man's favorite sayings.

Dad couldn't do any of that to me, though. We were far more alike than different, to the point that I shared his rare and dangerous talents. I was grateful for that, but I also knew it was one more reason why I, alone of my siblings and cousins, had to leave. This town wasn't big enough for the two of us.

I let him pick up on that thought and the associated memories that wreathed and colored it. I threw a little Wild West swagger into my gait as I approached his table. I let him know that while I was serious about the things that we disagreed on, I also had a sense of humor about them. The I remembered Victor, and let the humor curdle. I knew the things my Dad did to maintain order and impose his rules -- most importantly, the family's precious rule about marrying well outside our gene pool, a tough rule to follow when the town's culture was one of sticking close and staying put. It wasn't easy to meet new people. It was even harder to coax outsiders to come live here in this hellhole. No wonder Mom had up and left, especially given what a controlling bastard he was.

But he was my Dad. I loved him, I respected him. I even admired him despite my anger at the monstrous things he sometimes did. And the truth is, I couldn't his inhuman crimes against him as much as I wanted to in principle. I not only forgave him -- I understood him. I knew that in his position, I would probably make the same choices he had made. He kept the lid on things, when it would be all too easy for the whole town... the whole family... to boil over.

My own emotions were deeply conflicted, and I saw in his gaze that he had picked up on this, also. Well, good. I had wanted him to. That was why I let glimmers of those things seep out of me.

Some or most of the guests at the rehearsal dinner surely knew what was going on, but were ignoring it in the name of manners. Or maybe they really didn't notice; there was quite a lot of booze flowing, because -- well, that's another facet of life when you live among people who can pick up on your stray thoughts. Alcohol helps dull the roar, and also makes it feel less invasive when someone else's worries, obsessions, desires, and aggravations seep into your own consciousness. It was one among a million other reasons I left: If I hadn't of got out when I did, I'd of been permanently pickled by age 24. Like my lush brother Gil. Like Marisa, ever genteel with her goblets of red wine.

"Son," he said, when at last I stood before him.

"Dad," I said.

"So?"

"You know what I think."

"Not like I once did. You're too strong for that. But that's not the problem between us, is it? The problem is, you don't know what I think. Want me to explain it all to you again?"

"Every time you explain it, I see through it more."

"But it's true," he said. "You belong here with us. You should stay."

"No, I don't. I needed to get the hell out of here. Any young man would."

"But everyone else stays."

"Only because you have got them so freaked out about the world at large!"

"Your Aunt Clara is right," he told me. "Ordinary people live locked in their own minds. They don't know, and don't care, about the suffering of others. Their neighbors, their colleagues... their victims. Ordinary people are only capable of line-of-sight compassion, son. Ours is a heavier burden. We don't, we can't, feed on each other the way the deaf ones do."

"And, of course, it's such a noble sacrifice we make," I said sarcastically. "Staying out of the world because otherwise we'd affect their weak and tiny little minds. We'd act on their desires and fears, their weaknesses... all for their own good, of course. And they'd never even know how we plundered their thoughts for leverage over them... for knowledge of the rewards they crave and the words of assurance they yearn to hear. The strong ones, the ones like you and me, we'd simply control them from inside their own thoughts. Anyone else who can do what we do would manipulate them. Not us, we're too disciplined!

"But of course the thing that's whispered in the background is the fear that we wouldn't be disciplined. Not all of us. Not always. Over time, we'd become as corrupt as they are. We'd become the same kind of spiritual cannibals they are, feeding off the strength of those we dominated. And even if we somehow remained pure, it would come to the same thing: Out of noble intentions, we'd override their free will, and that would be ignoble. We'd end up becoming tyrants... we'd..." I sighed, irritation overwhelming me. "I mean, really? I don't. I live out there, and I don't manipulate people. I choose not to, and I abide by that choice."

"I'm proud of you for that, but not everyone has your strength of will or your character."

"Dad, it's common decency!"

"Not everyone would understand that."

"Nobody I ever knew here would want to take advantage that way," I argued. "If there's one good thing about living in each other's mental pockets, it's that we know the people in our own community through and through, and none of us are like that, Dad."

"But take their community away? Take away the accountability that comes with transparency of thought and motive? There are demons sleeping inside us, son. Those demons would wake up if we lived out there. Put a wolf among sheep, and he will slaughter. Sooner or later, his wolfish hunger will stir -- and he will slaughter."

"Dad, you hide behind that brick wall of yours. That mental brick wall that gives you an illusion of strength... invulnerability... kingship."

"I'm a steward, not a king."

I snorted. "Well, that slogan sounds nice, but it doesn't fool me. I'm your son. I see through that wall, and I see into you. There's something else. You want to tell me the rest of the story?"

He studied me, and I could tell he was listening very closely -- for a whisper of whatever suspicion or fact I might harbor. But I have walls of my own.

He smiled. "Yes, you are my son. That, more than anything, is why we need you here. Your aunt is right. My health is in decline."

"I'm waiting, Dad."

"Won't be sidetracked? All right, then. But keep what I've told you in mind. Our people are going to need your leadership."

"You're worried about succession? Why don't you make Marisa your heir apparent? She was always the eldest son you really wanted, anyway."

The old man's eyes flickered to her at her table, half-nodding over her latest drink. Gilbert was in even worse shape.

"All things considered," the old man said, in a surprisingly mild, resigned tone, "neither she nor your brothers are the fittest choice for the job." He slowly shifted is focus back to me. "And there are reasons for wanting you back that we haven't discussed."

I waited.

"We aren't the only ones, Ben."

I waited some more.

"You know how we came to Grant Hills. The Family chose to gather here, and to remain here. Back then, it was as much out of religious conviction as anything. We didn't seem so strange compared to any group, like the Amish or the Mennonites, who also wished to create enclosed communities. And yes, partly we retreated from the wider world for comfort, and for safety: It's easier to live among those like yourself, those who understand and know you. Those who have the capacity to know you.

"But it was also a matter of ethics," he added.

"Yeah, not imposing ourselves," I said dryly, quoting by rote from the same old song I'd heard him sing since forever.

"Not imposing ourselves, and not violating the privacy of others," Dad clarified. "How many times in a day or a week do you catch a thought or an intention and wish to intervene? Stop an assault, offer a word of hope?"

"What's wrong with that?" I asked.

"No, I won't have that discussion with you again. Not right now. I have another point to make, something you don't know. The Family gathered here, but only after disaster with The Others."

"The 'Others?' Regular people? One of their pogroms against us?"

"No, son, no -- far worse. More like a civil war. A telepathic war. You can't imagine it. Telepaths infesting the thoughts of other telepaths to drive them mad. Distracting each other at crucial moments, causing calamities, prodding and pinching, nudging and maddening... lives ruined, innocents killed and maimed... the strong telepaths projecting terrors... worse, projecting delights and desires. Sometimes the strongest combatants even decimated their foes physically, ravaging their brains -- "

"Like you did with Victor."

He paused, and I felt a flicker of guilt from behind his prideful blank wall. I expected a justification, an argument. Instead, all he said was, "Yes."

I went back to waiting.

"At the end of it, we just wanted a place to be safe and live in peace. So we brokered an agreement. The Family would stay here. The Others would go where they wanted, do what they wanted. As long as they left us alone, the peace would hold. That was almost two centuries ago. We've lived quietly, responsibly. They have not. You see what the results have been: Wars of convenience. Politics that devour instead of protect or serve. Monolithic corporations. Corrupt courts. The Others have manipulated the entire human race to the point of annihilation, all to enrich themselves."

I shook my head. "They haven't necessarily helped, but they aren't responsible for everything that's gone wrong," I said. "A lot of those problems are simple human nature, Dad. Not 'The Others.' Us, all of us. Human beings, telepaths and garden variety alike. Us and them."

"And how would you know?"

I got out my Intelliphone. I showed him the picture of Mark.

"Meet your son in law," I said. "Mark Clafferty. One of 'The Others.' He told me the same story you did about the war, but he has a different perspective on history. And he also has a different philosophy about how to live in the world than the selfish motivation you assign to all of his people. He doesn't interfere or intrude. He doesn't manipulate. Yes, the sociopaths among his people do all the things you're talking about, and they've made the world a little worse for it. But regular people still have free will, they still have minds of their own. Mark's people aren't mystics or supermen, and neither are we. They... we... might be able to influence, but they don't override people's own inclinations and desires. If we lived out in the world, we wouldn't either."

"They use human nature against humanity at large!"

"So do regular people. They're called politicians, Dad. Or zealots. Or salesmen, or saints, or creeps. But Mark doesn't go in for any of that. Neither do a lot of his people. Some of them tried to push society in a positive direction, but you know what? You'd be amazed how often their influence cancels out when other telepaths meet and match their influence. Or people's own deep-rooted fantasies and wants and needs neutralize the effect of their influence. Dad, regular people are almost nine billion in number, and how many of us are there? My god, you couldn't even keep mom here! And how hard did you try? Did your policy of not meddling in people's skulls stop you from trying to influence her to stay?"

He actually looked pained. "No," he said. "But I didn't try. Not consciously. If she wanted to go, I had no place stopping her."

"Except to steal her children. After you deliberately tried to use her as breeding stock to water down and wipe out our telepathic ability, which -- from what I've heard -- doesn't even turn out to be genetically transmitted."

"I was protecting you. You were going to grow up telepaths. You needed telepaths to teach you and guide you. You're right that genetics doesn't seem to be involved... we've tried for over a century to scrub a gene that evidently doesn't exist."

This was my family. These were the people they were, the choices they made. It drove me crazy. If that kid, Maisie's son, had happened by just then I would have taken two glasses off his tray, one for each fist, and I'd have self-medicated on the spot.

But here we were at long last, my dad and me, having a man to man. There were things I needed to know, starting with that day, all those years ago, and what I saw from the back seat of the squad car. Although I believed, and knew, that we weren't the danger to the world at large Dad feared we were, I'd still seen something that made me wonder.

"And Uncle Charlie? What did he do to her?"

"Nothing much. Just showed her what she really wanted. To be free of me, and everyone here. Everyone like us. You kids, too. He made her admit it. She left you of her own accord."

Well, there it was. She really did abandon us.

But so did I, so I couldn't cast any stones.

"You married one of them?" Dad asked. I couldn't tell if he was verging on anger or sadness.

"The minute we met, we both knew." Knew, I whispered, that we were like each other. And knew we were meant for each other.

"It's dangerous, son. He's dangerous."

"No, Dad. This is dangerous, what you do here. Pulling back, shutting out the world. The world is gonna find you no matter what. If you don't work to make it better -- really work, don't just sit back and think manipulative thoughts -- then it'll be so much the worse when it finally does catch up to you, here in Nutmeg Valley."

He looked at me, not convinced.

I looked right back, just as skeptical.

"What do you want from me?" I asked. "You want me to come back here and carry on with a... what, a cult, really, based on fear and some bullshit about 'ethics.' But you can see that things are changing. Once I left, didn't anyone follow?" I was sure they must have, but I didn't give him a chance to unfurl a manifest of names. Pressing on, I added, "Even your decree about marrying outsiders -- that was our A-1 sacred law, our Prime Directive, and that's gone by the wayside. We're at a wedding right now that wouldn't have been allowed before. From now on, people can marry who they want, live where they want... you can't stop freedom. Even if you're right somehow. Even if it's going to bring us all to ruin, us and them and everybody else."

I could tell he was tiring. Shit, he really must be sick, I thought to myself.

Then he surprised me. "I don't want to stop freedom," he said. "I only want to do what's best for our family. Setting aside the First Decree... It was hard, Ben. It's hard to face up to the fact that one of your deepest convictions has been completely in error. But to move forward, it's necessary to overcome ego, to take facts as facts and act accordingly.

"I don't know if you're right, Ben. I don't know if we can or should live among the rest of the world, or risk coming into conflict with the Others again. Maybe things have changed. I tend to think they have not... But I, Ben, I am the past. I can't guide our people to the future. They need someone young and strong. You're still the strongest of us, except for me. I won't be here forever. You need to come back, Ben. This isn't me being selfish. It's for the good of our community. You can't be selfish, either."

So there we were.

The wait was over. Finally, something from the old man that tasted of truth instead of tactic.

I kept my thoughts close to myself and sorted through them slowly. The room throbbed with laughter and shouts, music, and something else... an undercurrent of anticipation. Dad was right. Our people were indeed in need of leadership. Already, sensing him starting to slip away, they were becoming fearful.

The old man's eyes were still locked on me, calm and unreadable. I met his look and dug into it.

"If me assuming some sort of mantle from you... if that's what you really want from me... I don't know, Dad. I don't think it's necessary. I don't think it would be a good thing. But if I'm wrong... Look, I'll think about it. If the day comes that you can't carry on, and they really need me -- I'll think about it."

"Do that," he said, too proud to show his weariness, but that brick wall wasn't hiding it too well.

"There's something I want from you," I added.

Now he waited in his turn.

"Your blessing," I told him. "For Mark and me."

He smiled a half smile. "Son, you had that all the time," he said. "There's not much I could glean from you across all that distance, there's not even a lot I can glean from you up close. But what I could tell is that he makes you happy."

I gave him a skeptical look.

"You're my son," he told me, "but you're not as good as you think you are at keeping yourself to yourself. For that, there is only one true master, and I am he."

Keep telling yourself that, old man, I whispered, as he rose carefully to his feet and gathered his jacket. I shook his hand, and turned to make my way across the room, which now had been reconfigured, tables pushed aside to create a makeshift dance floor. Lansing caught my arm. "Ben!" he cried.

"Hey, baby brother," I told him.

"Meet my bride. Shana, this is my older brother Benjamin."

She's beautiful, I whispered to him. Then, You're beautiful, I whispered to her.

Shana smiled a radiant smile. Why thank you, she whispered back.

Kilian Melloy serves as EDGE Media Network's Associate Arts Editor and Staff Contributor. His professional memberships include the National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association, the Boston Online Film Critics Association, The Gay and Lesbian Entertainment Critics Association, and the Boston Theater Critics Association's Elliot Norton Awards Committee.