December 18, 2015

Broderick Fox Turns His Lens to 'Zen and the Art of Dying'

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 17 MIN.

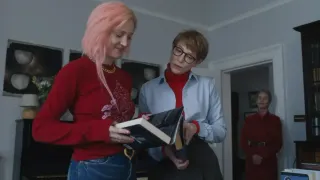

Openly gay documentary filmmaker Broderick Fox goes places others might not wish to venture, and does it with heart and grace. An early short documentary examined his brush with body dysmorphia (anorexia and compulsive exercise); his first full-length documentary, "The Skin I'm In," featured at film festivals around the country a couple of years ago, examined Fox's own experiences with addiction and alcoholism.

Now Fox follows up with "Zen and the Art of Dying," a project that took him to Australia to meet and film Zenith Virago, a self-trained "deathwalker" who has made a profession of helping people -- sick and well, young and old -- think about and prepare for the eventuality of shuffling off this mortal coil. It's a frightening prospect, of course, and not one that may people are eager to contemplate. But for reasons both practical and philosophical, the work Virago does is helpful and meaningful.

The film's press notes summarize Virago's vocation as follows: "From her origins as a young mother in the UK, to her present day identity as a lesbian, activist, and self-described deathwalker in the idyllic seaside town of Byron Bay, Australia, Zenith Virago's personal and professional experiences quietly challenge our core assumptions about life and dissolve our taboos around death..."

As Fox puts it, "She's helping us all prepare for our deaths and to return end-of-life decision making, funeral and burial options, and bereavement back to the home and back to community, rather than ceding these rights and rites to medical and commercial forces."

Fox, an Associate Professor of Media Arts & Culture at Occidental College, says that his film falls into a genre he terms "Body Media" -- a category that allows for examination of the many topics and issues that have come to be associated by many people with shame. (As a matter of full disclosure, I need to mention that I took the idea of "Body Media" as the starting point, and the title, of a short story published here at EDGE.)

That might not seem like a broad swath of territory at first blush, but upon consideration any number of issues present themselves: Sex and sexuality, age, physical ability or disability, conventions of beauty and athletic skill... In what ways are we not subjected to shame when it comes to our bodies?

Then there's the conceptual flipside to the notion, which is how people can turn their bodies into an artistic canvas for self-expression. In "The Skin I'm In," Fox retraced his journey from the abyss of addiction (following a potentially fatal incident in Berlin) to a state of recovery -- physical, mental, and spiritual -- that involved getting a huge tattoo over the course of a full year. That film ended with Fox sober, centered, and happily partnered.

The tattoo Fox commissioned can, of course, be seen in the light of "body media," but in the last few decades our culture has seen wave after wave of styles shake up the culture. Many of these trends seemed extreme at first - and some of them still do: Mohawks; piercings; scarification; branding; more extensive body modification, such as when people split their tongues or resort to surgery to becoming gender-neutral (or, in the parlance of those who have done so, "smoothies").

"Those all sound like amazing projects to me," Fox said when I listed the off-the-cuff roster of themes he could conceivably cover in the "Body Media" genre. "My mind is churning with all of them! I think I could probably be fascinated pursuing any of those topics."

But a filmmaker's vocation involves such a need for resources -- finances, time, focus -- that it's only over the course of a lifetime that one might hope to explore even a significant fraction of all the possibilities in the areas that interest him or her. In the case of "Zen and the Art of Dying," the project required travel all the way to Australia.

"The film actually is set in the easternmost community of Australia, a town called Byron Bay," Fox informed EDGE. The project, he added, centers on "a woman named Zenith (Zen) Virago -- the title is a play on words -- who is actually from the UK, but she's been in Australia the last 20-plus years, helping this community re-connect with dying and death, taking a real DIY [Do It Yourself], engaged, personalized approach -- dying at home, keeping the body at home for several days and washing and dressing it yourself, building and decorating a coffin yourself, providing cost-effective and environmentally sustainable body disposal options (cardboard coffins, green burials), making funerals meaningful again... in short returning death and its rituals to part of the communal life cycle. One of the most powerful aspects of this community's work for me was witnessing how children are permitted to be a part of the dying and bereavement process.

"We met Zenith when we premiered 'The Skin I'm In' at the Byron Bay International Film Festival," Fox continued. "She just happened to be in the audience. She came up to me afterwards, and we connected and she told me what she did, and as part of my critical writing around media I've been doing a lot of thinking about how people have been using video and social media to address a range of bodily taboos; I'd been specifically doing some writing that year about people mediating their stories around illness-related pain management and death and dying issues. It was pretty serendipitous when I ended up not only meeting a death worker, but one who also is a really engaging queer/feminist, colorful unapologetic character. I thought, 'I'm gonna have to make a movie!'

"I had a sabbatical in 2012," Fox recollected. "I went back and we literally lived with her for five weeks and followed her around as she did her professional duties, and got into the fabric of the community."

The task of making a documentary is in itself an object lesson in how one must tighten the subject, and pare content to a manageable serving.

"We shot a lot!" Fox exclaimed. "We were shooting every day, with the knowledge that we'd pretty much have to make a movie from whatever we got. I wasn't going to be able to afford to come back for any pick-ups. I would say I shot about 70 hours of footage for what turned out to be about a 75-minute feature documentary.

EDGE recalled how "The Skin I'm In" had Fox in front of his own camera lens, talking about his struggles with various forms of addiction, as well as issues such as cutting and OCD. The question arose as to how, and to what extent, the tattoo Fox came away with from that project continues to symbolize his health and wholeness.

"The tattoo is still so much a part of who I am and a part of my body... since it's on my back, I don't really see it every day. My partner is the one who has to stare at it. But certainly in terms of the principles it stands for - turning scars into art, the possibility for metamorphosis and personal transformation, the lifelong connections and friendships the process of its creation brought me -- those things continue to enrich and fuel me every day."

Even when he's not thinking about the skin he's in and the design that graces his skin, "the original design by Rande Cooke is framed and right next to my desk, so I do absolutely see the design on a daily basis in that way," Fox noted.

But the young filmmaker isn't focused on physical matters to the point of excluding everything else. Fox spoke to the need for a healthy integration of mind and body.

"I challenge the idea of fragmentation and disconnection from the self," Fox said, "and that there is any finite resolution to finding out who one is. I think it would be really disappointing if that were the case. I think we all continue to evolve.

"One of the things about autobiographical media is: The truths you tell at the moment of production are only specific to the person you are at that moment. We're always changing and evolving. The bigger spiritual journey is about finding some tools, finding a connection to something outside of self, that will help to approach and handle the inevitable slings and arrows of life. It's still a daily challenge -- being off drugs and alcohol you really start to get a feeling for what your baseline biochemistry and essential self are. Part of that, for me, is there is always going to be some level of anxiety. I think that energy that I'm calling anxiety in this moment can be a wonderful thing. That's the energy that fuels me creatively. In other moments, it could be described at passion, or dive; but it can trigger insecurities around work, with my teaching or things like that, and then it does take the form of stress.

"I think both 'The Skin I'm In' and this new project are chapters of what is going to be a lifetime-long journey of exploring the boundaries of the self. Our bodies, thoughts, feelings, and perceptions are all perpetually changing. If we're not our minds, if we're not our bodies, then what are we?' There is something that remains constant amidst all the ephemera -- some people call it awareness, perhaps consciousness, perhaps spirit? These meditations really start to come into focus when we confront the final Western bodily taboo -- death -- and truly acknowledge that our body/minds are going to die.

It's certainly the case that one encounters the philosophical outlook that it's the ending of a life that gives shape and meaning to that life. But how does the new film fit in with the work Fox has done before?

"This project is very much a continuation of my other work, even though it's not autobiographical," Fox said. "My work tends to focus on accessible characters who have taken chances in their own lives, who have found courage to look at things from a different perspective, and in doing so, have created ripples in culture beyond themselves."

"That includes a desire to tackle some of the really tough questions that you alluded to, and that we talked about before; the relationship between self and culture, the limits of the body and the mind, the meaning of existence, or the nature of consciousness? How can someone cultivate a sense of self and a connection to something larger? How do we get at some of those bigger questions through grounded accessible characters and story?

"In that sense, taking on illness or death and dying is a natural next progression my body media journey. I want to take on any topic where culture says 'Look away,' or 'We can't talk about that,' or 'We shouldn't address that.' Particularly in American culture, aging, illness, and death are considered not only bodily failures, bur personal failures. There is a lot of fear and shame associated with these issues.

"I came into this project not really having experienced that much illness or death in my own life," Fox added, "and so it's been an incredibly humbling and ongoing learning experience. Following Zenith for five weeks is not just following her, but walking into and being allowed into some of the most vulnerable and challenging life moments of a range of people in the community -- showing up at a young man's funeral and filming that, to show how a funeral can be done differently. Going to the living wake/birthday party of a 56-year-old woman who is in the end stage of cancer. Having a mother share how she ushered her young children through the death of their father. Zenith and the community model, what might best be described as states of grace in facing these issues -- showing that by tackling these things head on, understanding the truth of them rather than avoiding or denying them, there are ways of moving through pain and grief rather than getting stuck, frozen, or paralyzed, or perpetually damaged by these experiences.

"As Zenith says, death is a great teacher. There's an incredible amount of growth that can occur for the person dying and those left behind; an incredible amount that gets clarified around the meaning of identity, and the meaning of life, as you confront that."

Of course, we don't have anything along the lines of a "death walker" in America's mainstream medical culture -- though similar ideas are starting to take hold on the margins. In the main, however, our medical system is geared toward fending off a person's demise until the last possible millisecond. EDGE posed the question: Is Zenith Virago focused on the person who is approaching the end of their life, and helping them process the experience? Or is her role also to do with the wider community -- their family and friends, also helping them confront the end of a person's life?

"You know, it's both!" Fox replied. "The film tells the story of how she got into this work, and it's a pretty amazing story. She didn't have academic training or professional credentials to do this work. She was a young renegade woman who left the UK and found herself in Byron Bay in her 20s, which was back in the '80s, and first started working as a wedding celebrant, which is not really a term we have here. Even if we want a friend to marry us here in a non-denominational way, they still have to get "ordained" by some online ministry. It's still couched in some sort of religious terms.

"But in Australia and a number of other commonwealth countries there's a notion of the celebrant, somebody who has vested authority with the state to grant marriage licenses or officiate funerals. Zenith became the top marriage celebrant in this community of Byron Bay, and then a friend of hers died and she said, sort of in a spontaneous moment -- with the woman's husband, standing in the morgue -- she said, 'We don't need to hand this body over to other people. We can do it ourselves.'

"She proceeded, with the help of a professional funeral director, to figure out what the forms and paperwork were to take control of the body, bring it home, wash and dress it, keep it the house for several days so that people could come to terms with the physical reality of the death, build and decorate a coffin, transport that body to a park where there was an open air service that she led, and then ultimately to the crematorium. It was a three or four-day process, by the end of which she felt really elated. The grief was transformed for everybody involved, for having been a part of something greater.

"People in the community started to say, 'Can you do that for us?' And she has, for the last twenty years. So the work takes on a range of forms. She has a paralegal background, so she has a great balance of activist and practical and legal information, along with the spiritual and empathetic dimensions. She conducts workshops for people who want to work in death care, workshops for people who are dying and their family members. Through a number of grants she's received, she's traveling around Australia and doing training sessions so that other people can do this work in their communities."

It occurred to EDGE that for Fox, in particular, having come so close to dying himself, the experience of seeing what Zenith Virago does might have an especially enriching effect on his life.

"Absolutely," Fox said. "The door has been opened. Even on a level of practicality I know I've made some major steps: I've created an advance health care directive for myself and my partner, we've created wills, we've thought about the logistics of where you house these documents, who you share them with so somebody can find them. We've started to broach the conversations around end of life care and wishes with family members and friends. The channels of communication around this started to really open up."

For many people, of course, the very idea of having such conversations could feel awkward or even frightening.

"I think that death and dying get so sensationalized in the media," Fox said. "Either they're fictionalized and romanticized in some flowery way in film and television, or they get spectacularized and othered: casualties on the nightly news or murder and mayhem on film and in television shows."

One icebreaker for those conversations was, of course, the fact that Fox was actually making a movie about the subject.

"I wasn't really sure how people would respond to me saying I was making a film around re-engaging with dying and death," he confided. "To be honest, I think there always is an initial surprise, but quickly thereafter everybody has a personal story -- an illness of their own, the death of a parent, the death of a child or a friend. Very quickly the conversation gets to a profound level of intimacy and honesty, and that's been pretty amazing. I can't really think of any other topic for a film in which you could really jump into a deep conversation with people with that amount of speed. That has made me hopeful that the film will resonate with people and will help nudge audiences toward opening some of these doors and asking some of these questions.

"It isn't just about planning for death," Fox summarized. "[The act of making such plans] does take some thought about what the life is that you're living, and [raises the question of] are you living the life you're living? I think that is pretty profound."

Even for those of us who won't face the prospect of a terminal illness, life is in itself a terminal state of being -- as the old joke notes, no one gets out of it alive. The very passage of time carries with it a certainly from which we often shy away -- the disconcerting fact that each year gone means fewer years ahead.

"Dying isn't always about aging, but absolutely [the film] does tackle that question of what does it mean [to face aging], particularly to the American culture in which death aversion is linked in some profound ways to a disavowal of aging and, quite often, where illness or disabilities are described as body failures," Fox pondered. "Or, where the battling of disease is couched in militaristic terms: A war on X, Y, or Z, whatever the illness or the condition is. Some of that language, some of those metaphors are so steeped into our culture... hopefully the film will serve to get people to think about them, and see how much some of those ideas are kind of pre-conditioned and affect how they live their lives and think about their own bodily welfare."

What EDGE heard in this was that age and eventual death are not the enemies we're conditioned to believe they are. That might mean youth is not something to try to cling to -- and the passage of time is not something to fear.

"Some of the people in this film talk about the process of journeying through dying and death as a process of healing," Fox told EDGE. "There's an idea that one could die healed -- or one could live very much not healed. Healing and trying to achieve a sense of personal peace are really the end game of the people in this film, and I think that's been pretty inspiring."

"Zen and Art of Dying" is now starting to get some play on the film festival circuit.

"We had our World Premiere in March as the Closing Night Gala film of the 2015 Byron Bay International Film Festival," Fox recounted. "As Byron is the community the film documents, it was a sell-out crowd, with all the film's participants in attendance. Zenith Virago, the film's central subject, chose to wait and watch the film for the first time surrounded by the community she serves, which was both exciting and nerve-wracking, but we could not have imagined a more heartfelt response from Virago and the community.

"In September we screened as part of Cinema Diverse: the Palm Springs LGBTQ Film Festival. The film was among the 'Festival Favorites' chosen by audiences," Fox continued. "In October, we were at the Austin Film Festival, where we received warm response at our two festival screenings as an Official Selection of the 2015 Heart of Film Program -- a selection of 14 films expressly chosen to showcase diverse storytelling across a range of genres and forms. Zenith Virago flew in from Australia for the fest, and we conducted Q&As after both screenings!

"And we are just back from the Santa Fe Film Festival, where the film received a really fantastic response. It's exciting to see that Zenith's work is translating with American audiences. There is already interest for her to come and conduct workshops in Austin and Santa Fe."

Coming from Santa Fe, this EDGE correspondent had to interject that this didn't come as a surprise. Santa Fe is a place that tends to attract very open-minded, vibrant individuals who would love this.

"Yes, it's been exciting to begin travelling with the film and seeing that there are in fact a lot of people doing great work, similar to Zenith, here in the U.S.," Fox said. "Some call themselves death doulas or death midwives. There are green cemeteries opening up, and a range of home funeral and consumer's rights groups forming.

"All of this is part of a growing international Natural Death Care Movement that is gaining momentum as Baby Boomers begin to retire and are demanding more personalized, empowered, and meaningful choices around end-of-life matters, just as they did with the natural childbirth movement," Fox went on to note. "I've begun creating a list of resources on our Website (http://zenandtheartofdying.com) and welcome others to use the contact form to share additional organizations and links."

Fox added, "The film has been curated for screening at the Morbid Anatomy Museum in Brooklyn on Thursday January 14 at 8:00 p.m. This is an interesting cultural space that explores cultural, medical, and artistic histories of medicine, death, and corporeality. I'll be in attendance for a Q&A following the screening."

The inevitable question arose as to what Fox might be contemplating for his next venture.

"I'm really focused now on getting this film and its message out into the world," the young moviemaker responded. "And I'm also working on the second edition of my book 'Documentary Media: History - Theory - Practice.'"

However, Fox added, "I know another film will present itself when the time is right, and I look forward to that journey!"